Cotton in Ethiopia, East Africa

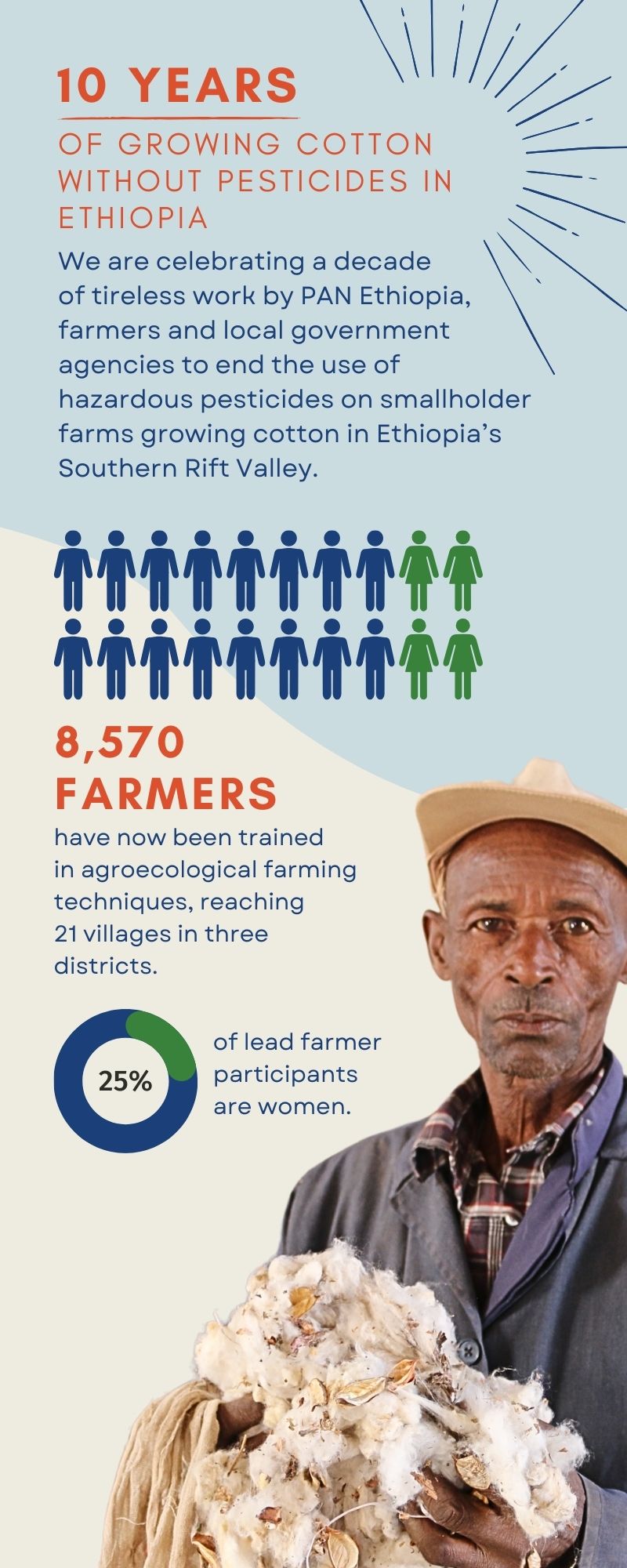

The Ethiopian cotton farmers trained in Integrated Pest Management (IPM) techniques, through our Farmer Field School programme, are thriving. Results have been beyond our expectations with lead farmers typically obtaining yields of roughly 30-50% higher than untrained farmers in the same area. These yields are being achieved without the use of harmful pesticides.

PAN UK has been working in partnership with PAN Ethiopia since 2013 to introduce sustainable cotton production to farmers near Arba Minch in southern Ethiopia. Good crop husbandry has increased the quality of the cotton and with PAN’s help, farmers are accessing new marketing opportunities for their cotton and many are securing a better price for it. Farmers are also improving their food security by growing a wider range of crops alongside their cotton. Combining up to date science with traditional local knowledge, the team works with farmers to identify the best crop combinations and agroecological practices to cope with increasing drought and changing rainfall patterns.

The support of local government agencies, especially the Departments of Agriculture and Co-operatives and the local Plant Health Clinic, has been invaluable in the project’s journey towards agroecological cotton in the Southern Rift Valley. Their involvement has also helped us to share agroecological methods with government field agents and farmers well beyond the project.

This project is funded by TRAID, a UK registered charity working to tackle the environmental and social impacts of producing, consuming and using clothes.

Phasing out Highly Hazardous Pesticides

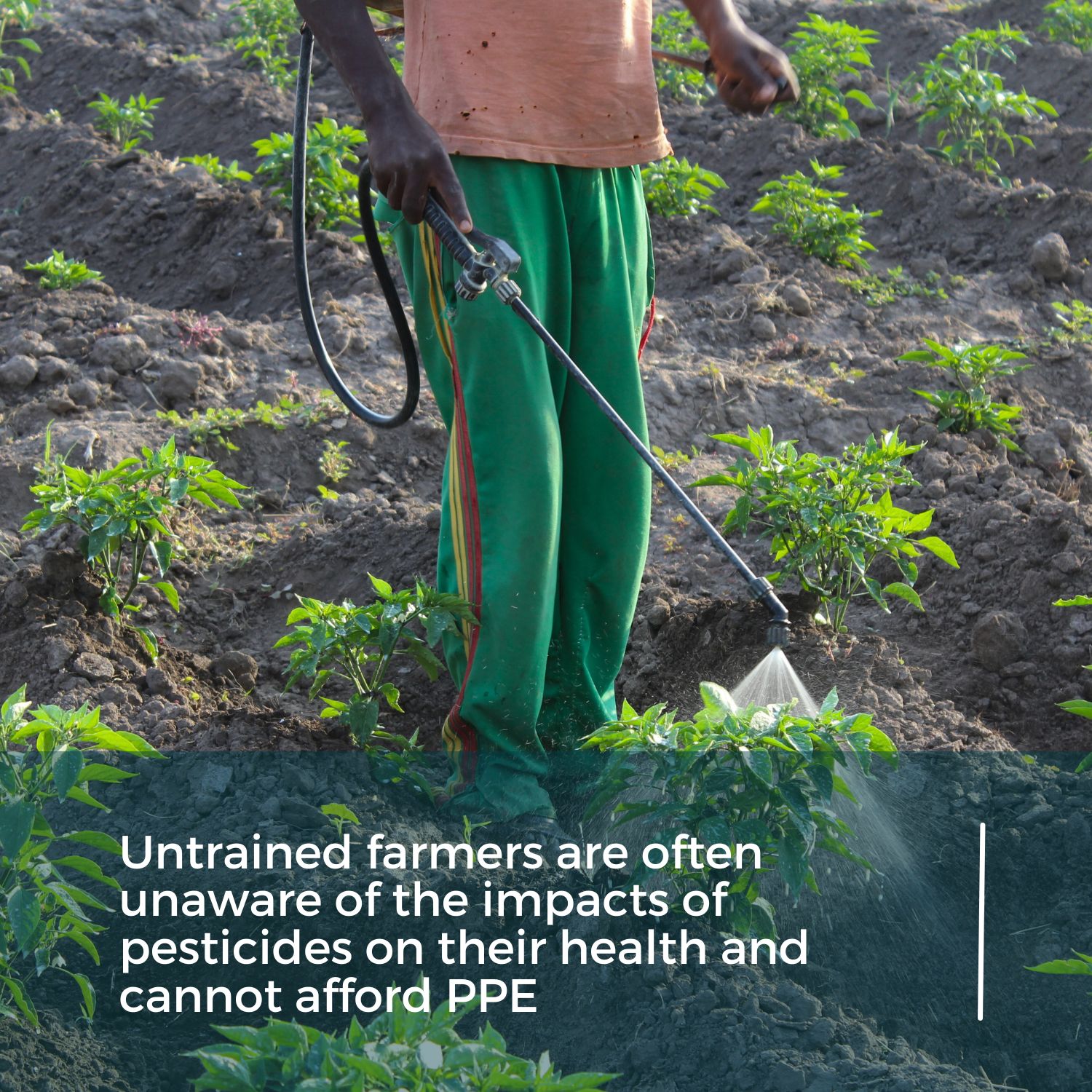

Cotton is grown by thousands of smallholder farmers in Ethiopia’s southern Rift Valley. Production can be challenging, as the crop is prone to attack by a wide variety of pests, especially African bollworm and sucking pests like aphids and whiteflies. Heavy pesticide use has had serious health and environmental consequences in the region. Weak enforcement of pesticide legislation, combined with aggressive marketing of hazardous pesticides, has allowed bad practice to become widespread.

When the project first started, Ethiopian cotton farmers often used extremely harmful chemicals classified as Highly Hazardous Pesticides (HHPs). Endosulfan, for example, was responsible for many deaths worldwide before it was listed for a global ban under the Stockholm Convention in 2011.

“We never used to be able to afford to wear protective clothing. Many of us now have shaking hands so our nervous systems must be affected. Children used to drink pesticides by mistake or after an argument with their parents. Any grass that had chemicals sprayed on it would kill our livestock and the residual effects could last more than a year.”

“We never used to be able to afford to wear protective clothing. Many of us now have shaking hands so our nervous systems must be affected. Children used to drink pesticides by mistake or after an argument with their parents. Any grass that had chemicals sprayed on it would kill our livestock and the residual effects could last more than a year.”

Admasu Wombera, Shelle Mela

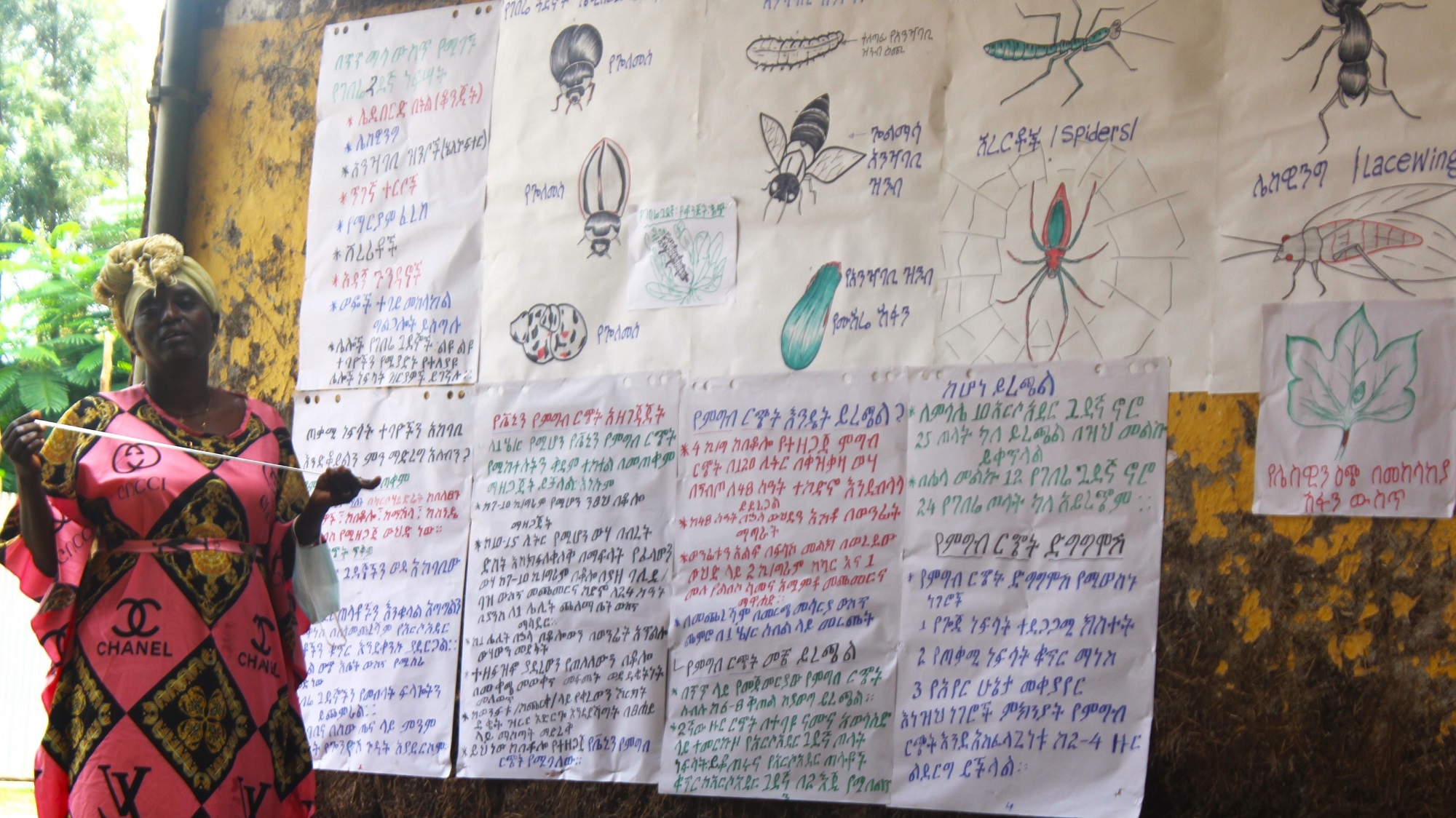

Community-led learning

Planting takes place when the rains arrive, usually around April or May. Before the growing season gets underway, farmers in the region are invited to join the Farmer Field School Programme. Using an allocated field as a practical, hands-on training plot, farmers are introduced to sustainable farming techniques over the entire growing season. They are made aware of the many economic costs of and harms caused by pesticides and are introduced to more positive alternatives for pest management.

The Farmer Field School approach works because it is not ‘top-down’ or prescriptive. It is a learning process open to examination, discussion and adaptation by all those involved. Participating farmers give up valuable time in order to attend regular sessions as they recognise the long-term benefits. Facilitators are often farmers themselves who return to their communities and share their learnings. A positive gender approach gives female farmers opportunities to gain confidence in interacting in mixed groups and ensures women’s voices are heard in discussions and planning.

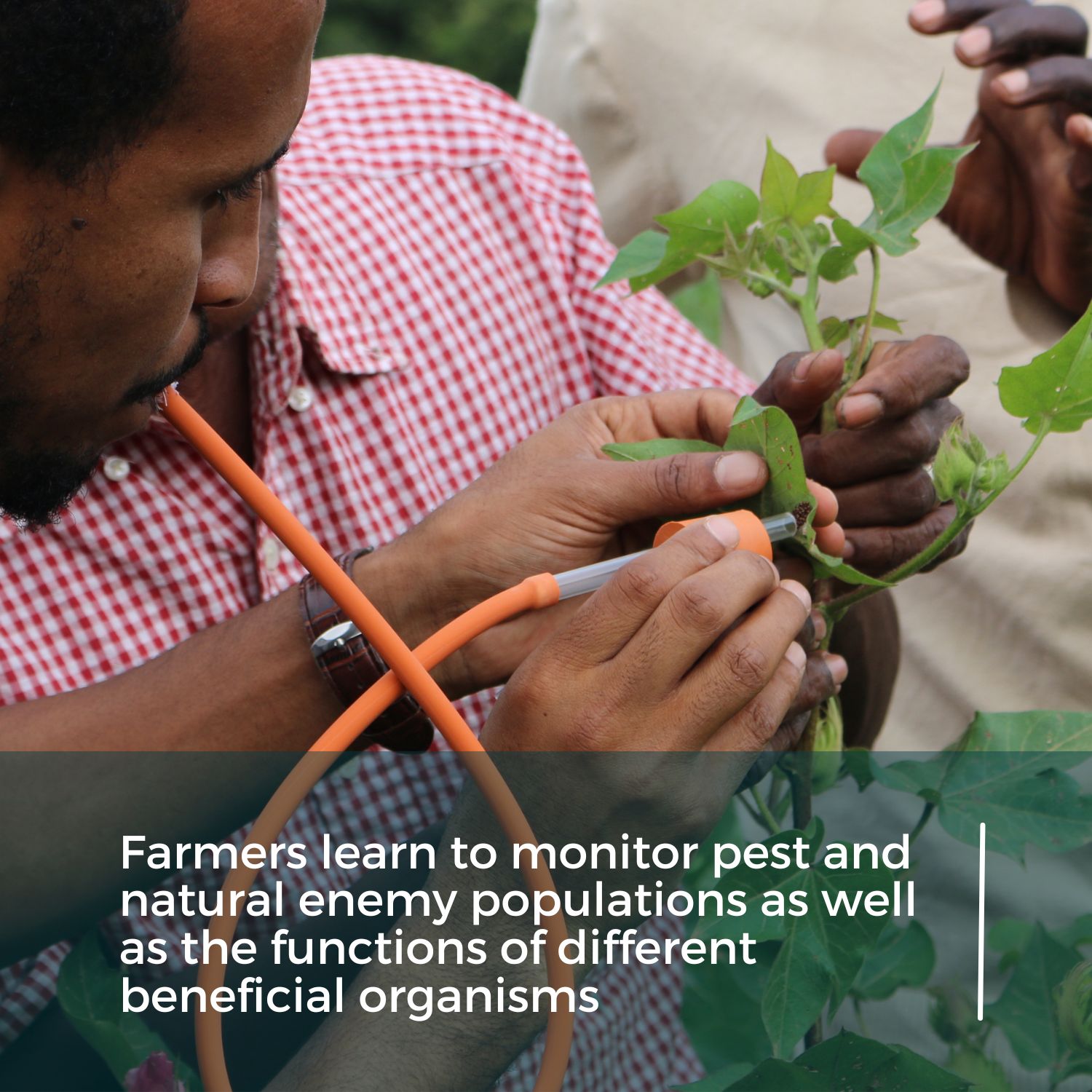

Working with nature

As the growing season gets underway, farmers learn to identify the difference between pests and beneficial insects in their crops. They assess and monitor pest thresholds and use tools and techniques to keep pests in check. Working with IPM expert, Dr Robert Mensah, PAN has developed an innovative food spray, made using cheap and locally available ingredients, which works by giving off a powerful odour that research has shown attracts predatory insects, such as ladybirds, predatory beetles, lacewings and hoverflies into the cotton crop. These act as a natural control over pest numbers.

In addition, farmers learn to monitor crop health, grow trap crops that divert pests away from the cotton, plant companion crops that provide refuge for beneficial insects, create healthy soil conditions and maintain high levels of field sanitation.

All of these techniques minimise the need for pesticide applications, protecting farmer, livestock, wildlife and environmental health.

Atalo Belay, PAN Ethiopia’s Programme Coordinator and Entomologist, talks about the innovative food spray method designed to encourage beneficial insects into the cotton crops in order to control pest species and reduce the need for insecticides.

Increased stability in uncertain times

Like many places around the world, southern Ethiopia is also suffering the effects of climate change and loss of biodiversity. Effects include increasingly frequent weather events, such as droughts and floods, alongside declining soil health and pollinator services. Training on agroecological farming methods has helped farmers better cope with this instability and to restore valuable biodiversity to their farms. Healthier and more diverse farming systems are better able to withstand erratic rainfall while healthier soils and pollinators are good for crops, too.

Many cotton farming households also grow vegetables for household needs and local sale. Since 2021, PAN Ethiopia has demonstrated that the food spray method used in cotton to boost numbers of predator insects to feed on pests can work in onions too. The team also promotes vermicomposting to support farmers to meet their vegetable crop nutrient needs with reduced reliance on commercial fertilisers. By feeding worms with crop waste, prunings and kitchen scraps, farmers are able to add the resulting compost to their crops. This free fertiliser helps to conserve soil moisture, builds below ground biodiversity in terms of soil dwelling organisms and helps to grow healthier crops that are better able to withstand pest and disease attack. It has potential to provide major cost savings.

The team is also exploring the pros and cons of different intercropping patterns, such as growing cotton with maize, beans or bananas, which can help spread risk of total crop failure and strengthen farmers’ resilience in adverse growing seasons. Agroecological cotton production requires confident, well-trained farmers who have developed an understanding of ecological pest management principles, gained field management and problem-solving skills and the ability to question and to adapt to changing contexts.

Image below: Farmers are trained to plant other crops, like banana or maize, alongside their cotton for increased food security.

Ethiopian organic cotton farmer, Debebe Demese, demonstrates how bees have returned to his fields since he stopped using pesticides. The return of bees provides an extra income for farmers as they are now able to keep beehives and sell the honey.

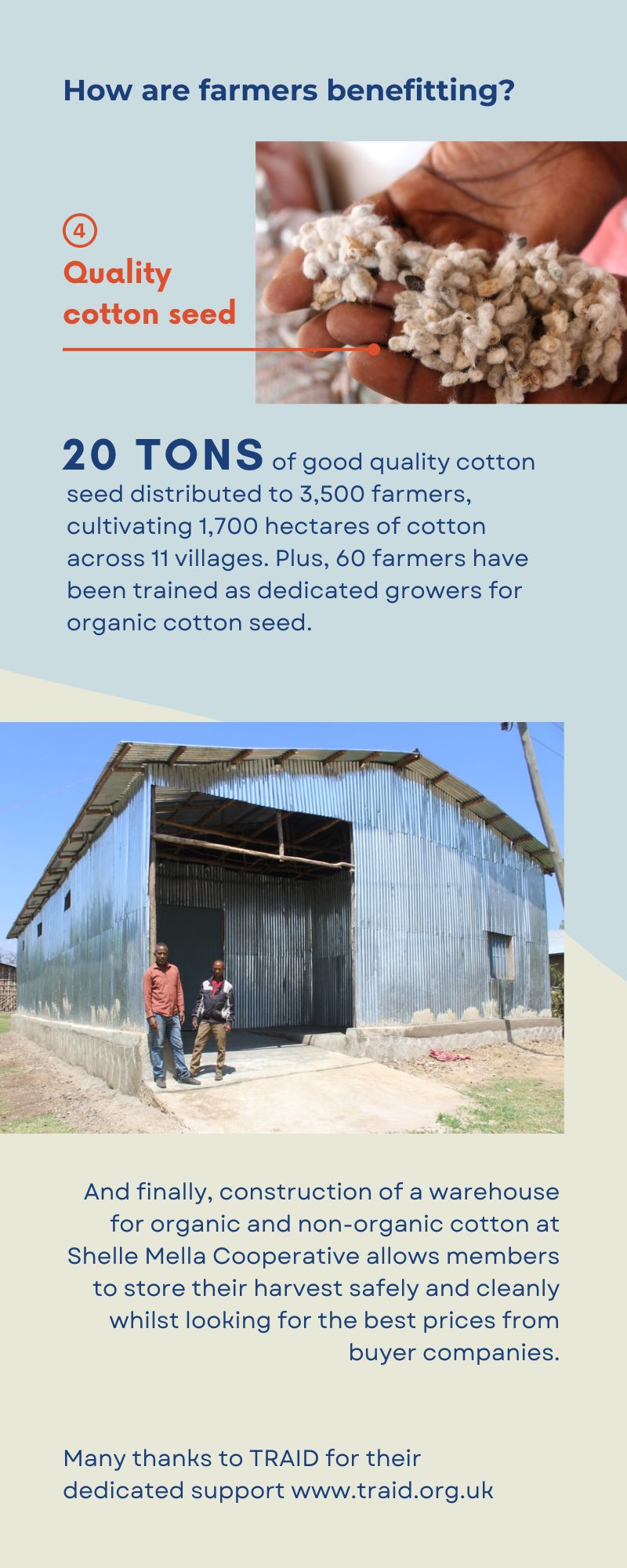

From harvest to market

Harvesting begins in the cotton fields in November with lead farmers currently obtaining yields of roughly 30-50% higher than untrained farmers in the same area. Farmers in Shelle Melle village formed a co-operative in 2015 and with the help of the project achieved organic certification in 2017, the first cotton farmers in the country to do so. There have been many benefits to members of the co-operative. As a group they have been able to secure a higher price for their cotton and build a warehouse for storing their cotton to organic standards.

“Our harvested cotton used to get ruined by rain and dust. The warehouse allows everyone to store their cotton in one place and to follow the correct procedures to avoid contamination of the organic lint.”

Mesafint Worku, Shelle Mela Cooperative Chairman

“We now buy maize in bulk which we can store in the warehouse and sell to Co-op members at a cheaper rate. Alternatively, farmers can buy the maize on credit and pay with cotton at the end of the season. They can also trade cotton for cotton seed to sow the following year.”

Ashenafi Tilahun, Shelle Mela Cooperative Member

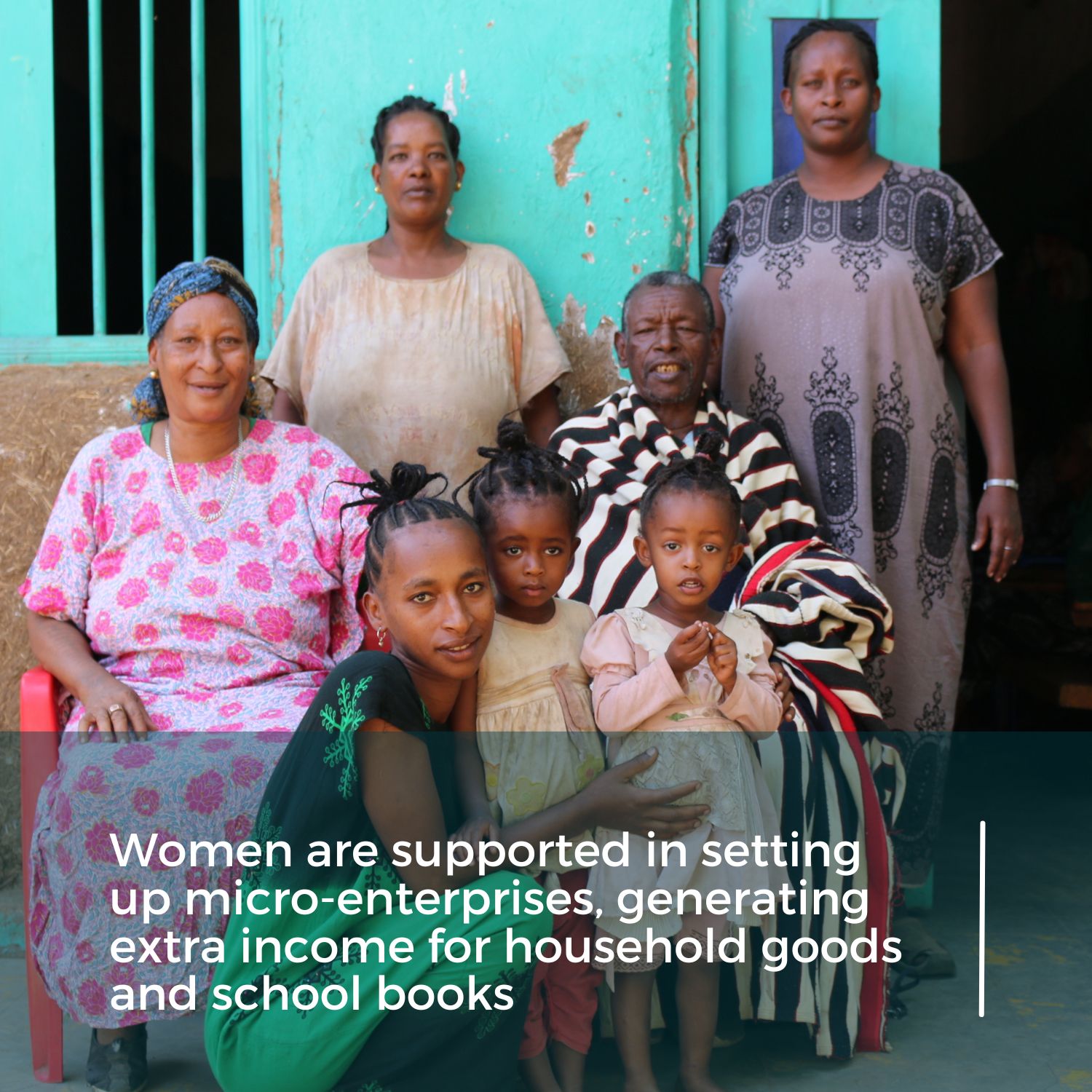

Supporting local women

Ten years ago, the number of women taking part in training was very low for a number of reasons. The team has worked hard to turn this around and, on average, 25% of participating farmers are now women.

The project has also supported women in setting up income-generating micro-enterprises. These include cotton spinning groups which bring women together in formal associations to increase yarn volumes and sales. They provide valuable extra cash, serve an important social function and give women an opportunity to improve their confidence and business skills.

Women have also set up cotton seed enterprises which clean and prepare cotton seed to sell to Farmer Field School farmers at a fair price.

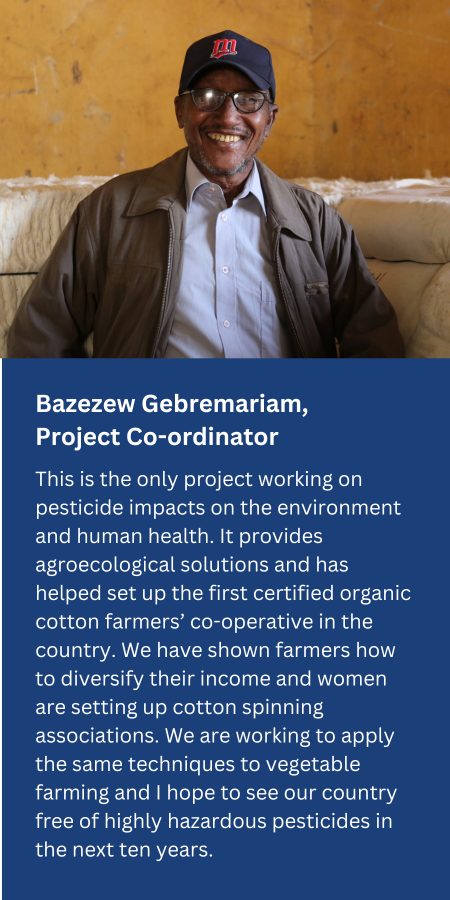

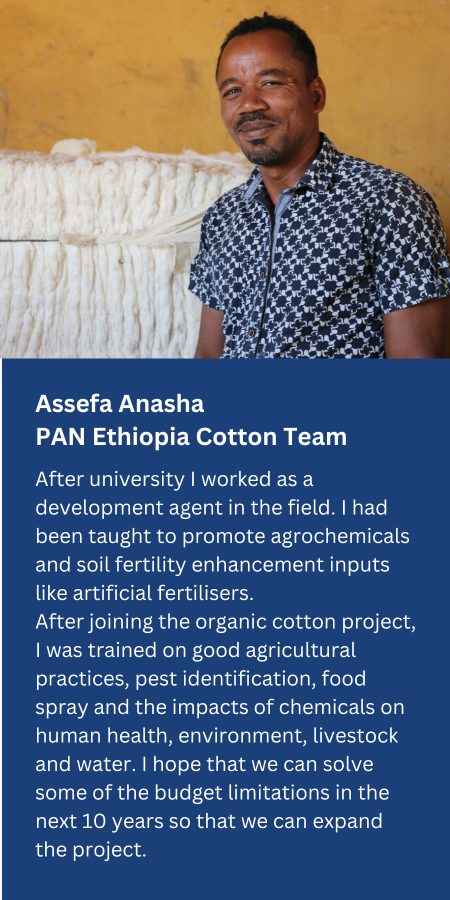

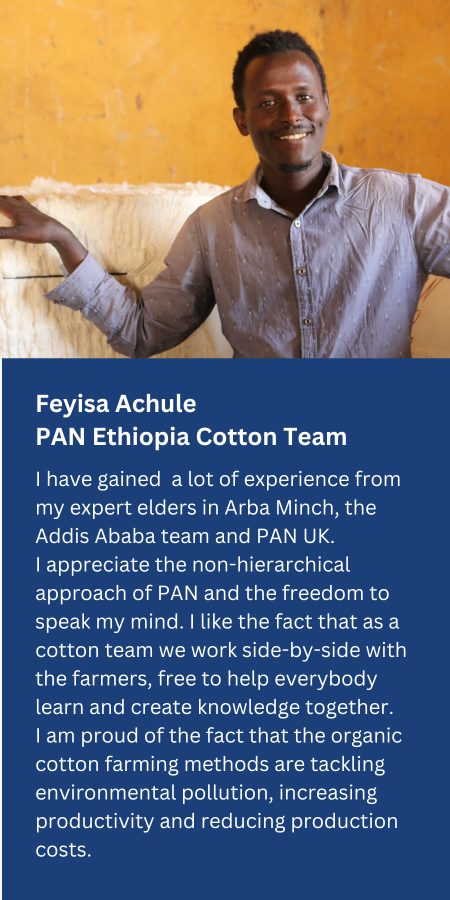

Meet the team in Arba Minch