Food for Thought

Children in England are being exposed to a cocktail of pesticide residues in the fresh produce they receive through the Department of Health’s School Fruit and Vegetable Scheme (SFVS). These pesticides have documented potential to harm human health, especially the health of young children who are particularly vulnerable to their impacts.

PAN UK has published the report, “Food for Thought”, with the intention of better informing parents and schools about the pesticide residues contained in the produce supplied to four to six-year olds in England under the School Fruit and Vegetable Scheme (SFVS).

Whilst we don’t in any way wish to alarm parents, or stop children eating the fruit and vegetables provided, we do believe that the scheme should be adopting a precautionary approach. Until we can say with complete certainty that these pesticides are not in any way harmful, we should not be exposing our children to them unnecessarily.

Our Findings

Our analysis of the last 12 years of residue data published by the Expert Committee on Pesticide Residues in Food (PRiF) shows that there are unacceptable levels of pesticides present in the food provided through the SFVS.

Residues of 123 different pesticides were found, some of which are linked to serious health problems such as cancer and disruption of the hormone system.

In many cases, multiple residues were found on the produce. This is another area of serious concern as the scientific community has little understanding about the complex interaction of different chemicals in what is termed the ‘cocktail’ effect.

We have also found that the levels of residues contained on SFVS produce are higher than those in produce tested under the national residue testing scheme (mainstream produce found on supermarket shelves).

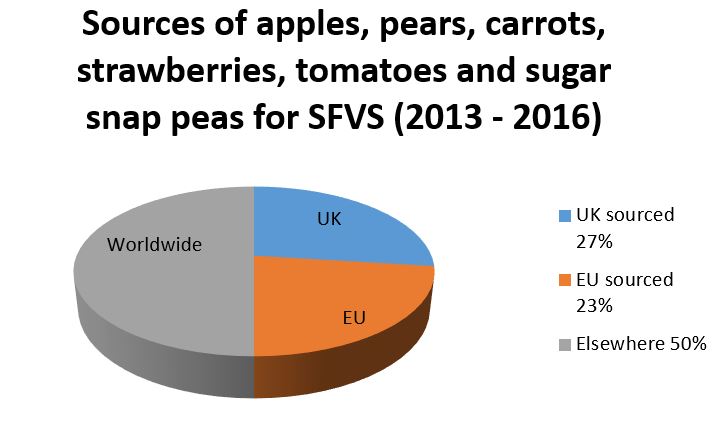

Only around 30% of the produce is supplied from UK growers. This is understandable with bananas, less so with apples. PAN UK would like to see more produce sourced from the UK and, specifically, from organic growers. The additional costs, according to our analysis, are not restrictive – approximately 1p per day per child. The benefits in terms of helping to grow the UK organic sector and protecting our young children from the effects of pesticides are priceless.

What can I do?

The UK is at a crossroads in terms of its relationship to pesticides.

The UK is at a crossroads in terms of its relationship to pesticides.

The EU’s pesticide regulations are among the strongest in the world and there is a real danger that, after Brexit, the government will choose to weaken those standards thereby increasing the exposure of the British public, including children, to potentially harmful chemicals.

However, the EU’s system is imperfect and Brexit is also an opportunity to move away from the current situation where it is almost impossible to avoid pesticide residues in our food.

After Brexit, the UK government should prioritise human health and reduce the exposure of the general public, and children in particular, to pesticides.

Find out more about our Brexit campaign here.

PAN UK is also urging the Department of Health to end its failure to engage in pesticide issues and take an active role in ensuring our pesticide laws stay strong once we leave the EU. If you’re concerned by pesticide residues in the School Fruit and Vegetable Scheme, then email Secretary of State for Health, Jeremy Hunt, and tell him to better protect our children by sourcing the produce from organic farmers.

Food for Thought - PRESS RELEASE

Food for Thought - FULL REPORT

Frequently Asked Questions

PAN UK is in no way trying to be alarmist by publishing this research. Rather, we are aiming to provide the public, in particular parents, with information that can help them make informed decisions. We also hope that parents and other concerned members of the public will use this information to lobby the UK government to do more to protect children from pesticides.

Adults and children alike are continually exposed to a vast range of chemicals. As an example, even within this relatively limited research study, some samples have tested positive for residues of up to 13 different pesticides. There has been little research into the combinatory or ‘cocktail’ effects of exposure to pesticides. As a result, we have limited understanding of how long-term exposure to this cocktail of pesticides affects human health. There is an increasing body of evidence showing that chemicals are more toxic when combined than alone.

We are assured by governments and companies that ingesting pesticides residues in food presents no unacceptable risk to us and our children due to the very low levels of any given active substance actually present. This assertion is based on the long-held tenet that “the dose makes the poison”, in other words that a substance will have harmful, toxic effects only if present in sufficient quantities. However, research in recent years has suggested that this assumption might not hold true for certain chemicals, such as pesticides, and that we should be concerned about the health impacts of certain chemicals at low doses.

Not at all. PAN UK recommends eating fresh fruit and vegetables as part of a healthy diet and as a way of encouraging long-term healthy eating habits. A good comparison is air pollution. We know, for example, that London’s air is polluted but would still recommend that children play and exercise outside for a healthy lifestyle. Despite the fact that there might be pesticide residues present, the nutritional value of the fruit and vegetables supplied through the SFVS remains unaffected. While we don’t know exactly how long-term exposure to a range of pesticides affects children’s health, we are certain of the immense benefits of eating fresh produce.

Washing fruit and vegetables is important to remove certain contaminants, particularly traces of soil which may contain harmful bacteria. However, washing is unlikely to remove all pesticide residues, although in some cases it might reduce the level found on the outside of an item. However, due to the systemic nature of many pesticides the residues are contained within the body of the produce itself and therefore washing the surface will not be able to remove all of them.

Where possible yes. However price and availability may sometimes make it difficult to maintain a completely organic diet. In fact, not all fruit and vegetables are equally susceptible to contamination by pesticide residues. Therefore, if cost or availability are an issue then switching to organic for those items that are most likely to contain residues is a good way of reducing dietary exposure to pesticides for you and your children.

Most people assume that no pesticides are used in organic farming, but, in fact, a limited range of pesticides are permitted. However, it is important to note that organic farming takes a completely different approach to the use of pesticides compared to conventional farming. Most of the pesticides approved for use in organic agriculture are from natural origins, such as beeswax, plant oils and pheromones. Pesticides are also not routinely applied. Permission has to be sought for their use and will only be granted if it can be proven that all other alternatives have been unable to contain the problem. As a result they are used in much lower quantities. In the EU there are currently 491 approved active substances1 approved for use as pesticides, of these only 28 are approved for use in organic agriculture.

If a substance is classified as a known carcinogen for example, it does not automatically mean that exposure to it will definitely result in the development of cancer. The classification simply means that in tests for toxicity the substance can cause a particular effect. There are many factors that influence our response to chemicals other than just our exposure to them, including genetic susceptibility. The length, quantity and frequency of exposure also affect likelihood. However, we simply do not know enough to be able to categorically state that dietary exposure to carcinogens and other chemicals will not have negative long-term effects on individuals. PAN UK believes that eliminating exposure to such chemicals, where it is possible to do so, such as in the SFVS, is the precautionary and correct way to proceed.

We compared the costs of organic and non-organic produce available from UK wholesalers price lists. The comparison is, of necessity, a snap-shot in time given that commodity prices fluctuate. We looked simply at the price difference between a kilogram of non-organic and a kilogram of organic for the same produce. Our analysis was not all-inclusive, in as much as we did not go to every wholesaler. The various prices reflected in the report were taken from the following websites and were, on the whole, indicative of the median cost for the product. PAN UK has no relation to any of the companies mentioned and we did not discuss their prices with them.

At present approximately 30% of the produce for the SFVS is sourced from the UK. PAN UK is advocating that, where possible, more of the produce is supplied by UK organic growers. For example, at present, some of the apples and pears supplied to the SFVS are sourced from Portugal and Belgium. Sourcing them all from the UK would help to reduce food miles.

The SFVS is funded by the UK Department of Health. The UK Government took the decision to opt out of EU funding for the scheme. PAN UK does not know why this decision was taken.

Given all the uncertainties surrounding Brexit this is difficult to answer with any clarity. But many are predicting that the cost of food will rise. As much of the food on the scheme is sourced from the EU it is likely that prices would rise. Without switching to a greater percentage of UK sourced produce, the costs for supplying the SFVS post-Brexit could rise significantly.

With Brexit looming, the UK has a choice. We can lower our pesticide standards, thereby increasing our exposure to potentially harmful chemicals. Or we can use Brexit as an opportunity to move away from pesticides and increase support to British organic farmers. This would better protect human health and enable a genuinely-sustainable agriculture sector to flourish.

In addition to urging the UK government to provide more support to the British organic sector, PAN UK has compiled a list of ten policy recommendations for the UK Government post-Brexit. If implemented, these changes would reduce the use of pesticides and the harmful effects that such use can and does have on the people and environment of the UK.

Our policy recommendations are laid out below and further details of our proposals can be found here.

- Introduce clear quantitative targets for reducing the overall use of pesticides in agriculture.

- Ensure authorisations are based on a strict interpretation of the precautionary principle; maintain a hazard-based (rather than revert to risk-based) approach to pesticide authorisations and phase out the most Highly Hazardous Pesticides.

- Do not authorise, or grant re-approval for, products which pose risks to human or environmental health where safer non-chemical methods are available.

- Fast track authorisation of less hazardous pest management products such as bio-pesticides.

- Introduce strong penalties and robust enforcement to ensure that any contamination of the environment by users of pesticides – including farmers and amenity users – is dealt with properly and will act as a deterrent to misuse.

- Create a human health monitoring system for those that routinely work with pesticides, including farmers, farmworkers and amenity operatives and establish a reporting system for others exposed to pesticides including the general public, farming families and rural residents.

- Provide incentives for reducing the use of pesticides and establish a proper monitoring system for pesticide use based on frequency of application.

- Introduce a Pesticide Levy and use the revenue raised to support programmes to help farmers reduce pesticide use.

- Establish a new body for monitoring pesticide use and enforcing pesticide regulations which is separate from the body that deals with pesticide authorisations

- Introduce greater transparency to allow independent scrutiny of toxicological and other data prior to authorisation of any active substance or formulation in order to break the undue influence of agrochemical companies.

Yes we can! A study published in 2016 titled “Organic Agriculture in the 21st Century”, shows that organic agriculture could feed the growing world population.2 A switch to organic is not going to happen overnight, but there are many things that could be done to reduce the use and impact of pesticides in the meantime.

2 “Organic Agriculture in the 21st Century” – John P. Reganold & Jonathan M. Wachter – 03/02/2016