The Cocktail Effect

UK citizens and the natural environment are being exposed to potentially harmful mixtures of pesticides. These mixtures appear in our food, water and soil and can affect the health of both humans and wildlife. There is a growing body of evidence that pesticides can become more harmful when combined, a phenomenon known as the ‘cocktail effect’.

Despite this, the regulatory system designed to protect us from pesticides looks at individual chemicals and safety assessments are only carried out for one pesticide at a time. This not only ignores the potential risks to human health associated with pesticide mixtures found on one item (an apple, for example) but also those contained in an entire dish or days’ worth of food. The system also ignores the cocktail effect when it comes to environmental protection, failing to monitor or limit the sum total of pesticide residues to which the environment and wildlife are exposed.

Pesticides appear in millions of different combinations in varying concentrations in our food and landscape. It is arguably impossible to create a system sufficiently sophisticated to be able to assess the full spectrum of health and environmental impacts resulting from long-term exposure to hundreds of different pesticides. The only way to minimise the risk to health and environment is therefore to hugely decrease our overall pesticide use, thereby reducing our exposure to pesticide cocktails.

Our new report, co-authored with the Soil Association, examines for the first time to what extent the cocktail effect is a problem in the UK and the potential impact upon human health and the environment. It describes the failures of our regulatory system to protect us from the cocktail effect and makes recommendations for what needs to change.

Key findings | FAQs | Video

Key findings

Pesticide cocktails are a significant problem in the UK

a) Food and health

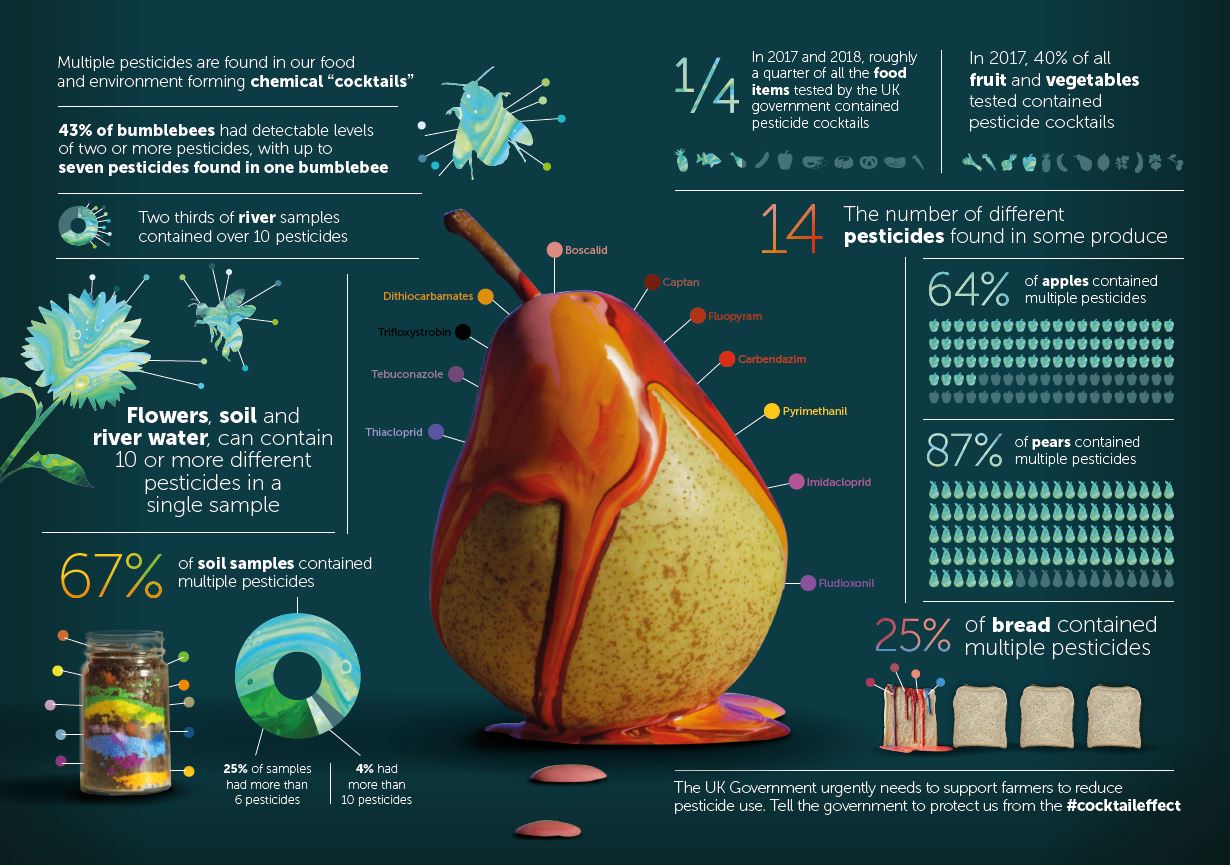

- Over a third of all the fruit and vegetables tested by the UK government in 2017 and 2018 contained residues of more than one pesticide.

- In 2017, 87.5% of the pears tested contained pesticide cocktails, with 4% containing residues of nine or more different chemicals.

- 55% of raspberries tested were found to contain multiple pesticides, with one sample containing four known, probable or possible carcinogens, two endocrine disruptors which interfere with hormone systems, one developmental toxin which can have adverse effects on sexual function and fertility and one neurotoxin which can negatively affect the nervous system and nerve tissue.

- Multiple residues were found in more than three-quarters of grapes tested in 2018, with one sample containing traces of fourteen different pesticides.

Pesticide cocktails are not only found in fruit and vegetables. In both 2017 and 2018, roughly a quarter of all food items tested by the government (which include animal products and grains) contained pesticides cocktails. In 2017, this included more than half of rice and a quarter of bread.

b) Environment and wildlife

There is currently no official government monitoring of pesticide cocktails in the environment and the only information available is from a small number of independent academic studies.

- One UK study found that 43% of bumblebees had detectable levels of more than one pesticide, with traces of seven pesticides found in one individual.

- A study of soil in 11 European countries revealed that around 67% of the UK soil samples had multiple residues, 25% had more than six, with around 4% continuing traces of more than ten pesticides.

- UK water appears to be no less contaminated. A study revealed that 66% of water samples taken from seven river catchments contained over ten pesticides. Two small rivers in East Devon were found to contain residues of up to 24 pesticides and six veterinary drugs.

Pesticide cocktails can be significantly more harmful than individual chemicals

Several pieces of research conducted on human cells and tissues have highlighted that combined actions of pesticide mixtures can lead to the creation of cancer cells and disruption of the endocrine system, which produces hormones that regulate metabolism, growth and development, tissue function, sexual function, and reproduction, among other things. Studies conducted on mice and rats have revealed similar results. Pesticide mixtures have been associated with obesity and impaired liver function, even when the doses of individual chemicals are below the safety levels set by regulators. Studies looking at insects, fish and birds echo these results. A recent study has shown that a certain insecticide touted as a ‘safe’ replacement for neonicotinoids and a commonly used fungicide combine to be more toxic to bees than when they appear alone.

What needs to happen?

The UK’s planned departure from the European Union provides an opportunity to put in place measures to support farmers to significantly reduce pesticide use and transition to agroecological systems, which place robust Integrated Pest Management (IPM) at their heart. In particular, the government should ensure that payments under the new Environmental Land Management Scheme (ELMS) encourage farmers to adopt non-chemical alternatives.

Leaving the European pesticide regime also presents some major threats to UK pesticide protections which could lead to an increase the exposure of the public and environment to potentially dangerous pesticide cocktails. It’s crucial that the government ensures that no weakening of UK pesticide regulations or standards occurs as a result of Brexit, including through trade negotiations with non-EU countries, and that in turn food imports meet these same UK standards.

Frequently Asked Questions

Despite the prevalence of pesticide cocktails, and the evidence that they can be more harmful than individual pesticides, the UK continues to assess the safety of one chemical at a time. Safety assessments of pesticide residues in our food continue to be based on analysis of individual chemicals, ignoring the potential risks to human health associated with pesticide mixtures.

While the government conducts extremely limited testing for pesticide cocktails in food, it fails to assess or limit the sum total of pesticides to which the environment and wildlife are exposed. There is no monitoring for pesticide cocktails in soil or the extent to which pollinators or other wildlife are being exposed.

Despite being acknowledged as a significant problem almost two decades ago, the UK regulatory system largely fails to even monitor, let alone protect us, from the cocktail effect.

Pesticides appear in millions of different combinations in varying concentrations in our food and landscape. While various efforts are underway by researchers to create a system capable of monitoring the cocktail effect, it is unlikely that any will be sophisticated enough to accurately assess the full spectrum of health and environmental impacts of pesticide cocktails. The only way to minimise the risk to health and environment is therefore to hugely decrease our overall pesticide use, thereby reducing our exposure to pesticide cocktails.

Over time plants, pests and diseases can develop resistance to the pesticides used to control them – meaning that these pesticides are no longer effective at dealing with the particular problem. One of the main strategies currently employed to deal with resistance is to use a wider range of active ingredients to avoid pests and diseases developing resistance. However, this leads to a greater number of actives being applied to food crops and subsequently released into the environment, exacerbating the cocktail effect.

While using a smaller a number of pesticides is therefore not the answer, there are strategies available that enable farmers to reduce both the risk of exposure to pesticide cocktails and the build-up of resistance. Adopting the methods and principles used by organic growers, such as varied rotations, selection of pest and disease resistant varieties and increasing the numbers of beneficial insect predators can all help reduce both the quantity and variety of pesticides applied.

Our current regulatory system focusses solely on assessing the risk posed to human health by individual pesticides, failing to account for interactions between multiple chemicals. Pesticides are tested in isolation for harmful effects and are not looked at in combination. This system not only fails to protect us from the cocktail effect, it completely ignores the issue.

This is a serious shortcoming. We are being exposed to cocktails of multiple pesticides via dietary intake and yet almost nothing is known about how these chemicals are interacting or the potential health effects of this repeated exposure.

Washing or peeling fruit and vegetables can potentially reduce exposure to pesticides as some residues that appear on the surface will be eliminated, particularly traces of soil which may contain harmful bacteria. However, although washing or peeling will reduce the level of pesticides found on the outside of an item, they are unlikely to remove all pesticide residues. This is because many of the pesticides used are ‘systemic’, meaning that they are actually absorbed by a plant when applied to seeds, soil, or leaves and the residues are therefore contained within the body of the produce itself.

The government’s testing scheme tends to show citrus fruit as having the highest residues. This is often because of its peel – fruit such as oranges and grapefruits, will show higher residues than are actually being consumed. Having said that, people are increasingly using the zest of citrus fruits. In addition, handling of fruit covered in fungicides (which are used to prevent food rotting) can mean dermal absorption (i.e. through the skin) is a problem, particularly for children.

While pesticide cocktails tend to be more commonly found in fruit and vegetables, they do feature in other types of food. In both 2017 and 2018, roughly a quarter of all food items tested by the government (which include animal products and grains) contained pesticides cocktails. In 2017, a quarter of bread contained pesticide cocktails as did 53% of rice, with 4% of rice containing residues of nine or more different pesticides. One sample of rice contained three known, possible or probable carcinogens, two endocrine disruptors and one developmental toxin. A quarter of bread contained multiple pesticide cocktails. In 2018, just under a fifth (18.75%) of the 288 samples of bread and wheat tested by the government contained multiple residues.

If a substance is classified as a known carcinogen for example, it does not automatically mean that exposure to it will definitely result in the development of cancer. The classification simply means that in tests for toxicity the substance can cause a particular effect. There are many factors that influence our response to chemicals other than just our exposure to them, including genetic susceptibility. The length, quantity and frequency of exposure also affect likelihood. However, we simply do not know enough to be able to categorically state that dietary exposure to carcinogens and other chemicals will not have negative long-term effects on individuals. This is particularly true of pesticide mixtures which, despite their prevalence, are largely ignored by the regulatory system designed to protect us. Given the huge uncertainty, eliminating exposure to such chemicals, where it is possible to do so, is the precautionary and correct way to proceed.

Brexit presents both significant threats and opportunities in terms of addressing existing concerns around pesticide cocktails. Despite government promises to the contrary, the UK’s exit from the EU threatens to significantly weaken UK pesticide standards. This could potentially lead to a major rise in the number of active substances authorised for use in the UK, as well as an increase in the level and variety of pesticides permitted to appear in UK food. Both of these outcomes would increase the exposure of the public and environment to potentially dangerous pesticide cocktails.

Brexit also presents a number of opportunities to introduce new measures to drive a reduction in pesticide-related harms and lessen the reliance of UK agriculture on chemical pesticides. These include adopting a pesticide reduction target and introducing measures to support UK farmers to transition to whole farm agroecological systems that include genuine and holistic Integrated Pest Management (IPM).

The UK government urgently needs to adopt the following key recommendations (the full list can be found in the report):

- Ensure that no weakening of UK pesticide regulations or standards occurs as a result of Brexit, including through trade negotiations with non-EU countries, and that in turn food imports meet these same UK standards.

- Introduce measures to support UK farmers to transition to whole farm agroecological systems that include genuine and holistic Integrated Pest Management (IPM), of which organic and agroforestry are well defined examples. Most notably:

- Use future farmer payments under the Environmental Land Management Scheme (ELMS) to incentivise and reward farmers.

- Create a new independent extension service for research, development and dissemination of IPM techniques.

- Facilitate farmer-to-farmer learning on agroecology and IPM.

- Introduce a clear, quantitative target for significantly reducing the overall use of pesticides in agriculture.

- Phase out all non-agricultural uses of pesticides and ban public authorities from spraying next to homes, schools and playgrounds.

- Establish robust environmental and human health monitoring systems for pesticide use which moves beyond the focus on individual pesticides and is able to assess combined toxic load.

Conduct government-funded research into the effects of pesticide cocktails on the natural environment, wildlife and human health.

Given the wide variety of different active ingredients used in food production, pesticides almost always appear in mixtures, commonly referred to as ‘pesticide cocktails’. These mixtures appear in our food, water and soil and can contain residues of as many as fourteen different pesticides.

There is a growing body of evidence that pesticides can become more harmful when combined, even when each individual chemical appears at levels at or below its “no-observed-effect-concentration”. This phenomenon is known as the ‘cocktail effect’.

The cocktail effect is a significant problem in the UK which demands urgent attention. Over a third of all the fruit and vegetables tested by the UK government in 2017 and 2018 contained residues of more than one pesticide. Pesticide cocktails are not only found in fruit and vegetables. In both 2017 and 2018, roughly a quarter of all food items tested by the government (which include animal products and grains) contained pesticides cocktails. In 2017, this included more than half of rice and a quarter of bread.

The evidence of pesticide cocktails in the environment is no less concerning. One UK study on bumblebees found that 43% had detectable levels of more than one pesticide, with traces of seven pesticides found in one individual. A study of soil in European countries found that 67% of the UK samples had multiple residues, 25% had more than six, with around 4% continuing traces of more than ten pesticides. UK water appears to be no less contaminated. Research reveals that 66% of samples taken from seven river catchments contained over ten pesticides.

There is a growing body of evidence showing that pesticide cocktails can have significantly more harmful effects than individual chemicals, even when each appears at levels at or below its “no-observed-effect-concentration”. Health effects revealed include obesity and impaired liver function, the creation of cancer cells and disruption of the endocrine system. Studies looking at insects, fish and birds echo these results. In just one example, a certain insecticide touted as a ‘safe’ replacement for neonicotinoids and a commonly used fungicide were shown to combine to be more toxic to bees than when either chemical appears alone.

“Particularly concerning is the way multiple chemical exposures can combine and interact with each other to impact health. Yet the few risk assessments that have been completed focus on the risk of exposure to individual substances, and don’t consider the human rights of the child.”

Interview with UN Special Rapporteur on Toxics, Baskut Tuncak, June 2019